Long-Standing Traditions

We are the Xwémalhkwu , the “People of the of the fast-running waters”, referring to the many rapids and rivers located within the unceded Xwémalhkwu territory. Our ancestral tongue is ayʔaǰuθɛm, from the Salishan language family. We are the descendants of the ancestors who survived the Great Flood by tying their canoes to the top of Paʔɬmɩn̓ (Place that Grows), known by many today as Estero Peak. We are the stewards and protectors of the land, water, and resources located from Hornby Island and north to Call Inlet, including Campbell River and other portions of Vancouver Island, over the Discovery Islands to East Redonda Island and up Toba Inlet to Brem River, and the Bute Inlet to Tatlayoko Lake, and the surrounding areas.

Xwémalhkwu People have occupied, controlled, and benefitted from these lands, waters, and resources since time immemorial, co-existing beside our sister Nations within the ayʔaǰuθɛm language group: K’omoks, Klahoose, and Tla’amin. We also recognize the recent arrival of the Liqʷiłdaxʷ people, who now share a responsibility to the land, water, and resources with Xwémalhkwu in portions of Xwémalhkwu territory. There are 495 people registered with the Homalco Band today.

Culture Almost Lost

The first missionaries to visit Xwémalhkwu territory were the Oblate fathers in the late 1860s. This would mark the start of a sad history for the Xwémalhkwu people. Forced to burn all regalia, masks and carvings in their possession, the Xwémalhkwu were banned from holding ceremonies and practicing traditional songs and dances. Our ancestors spoke their language in secret to avoid consequences from the Oblate fathers. It was at this point that Xwémalhkwu peoples were forced to learn and adopt Christian rituals.

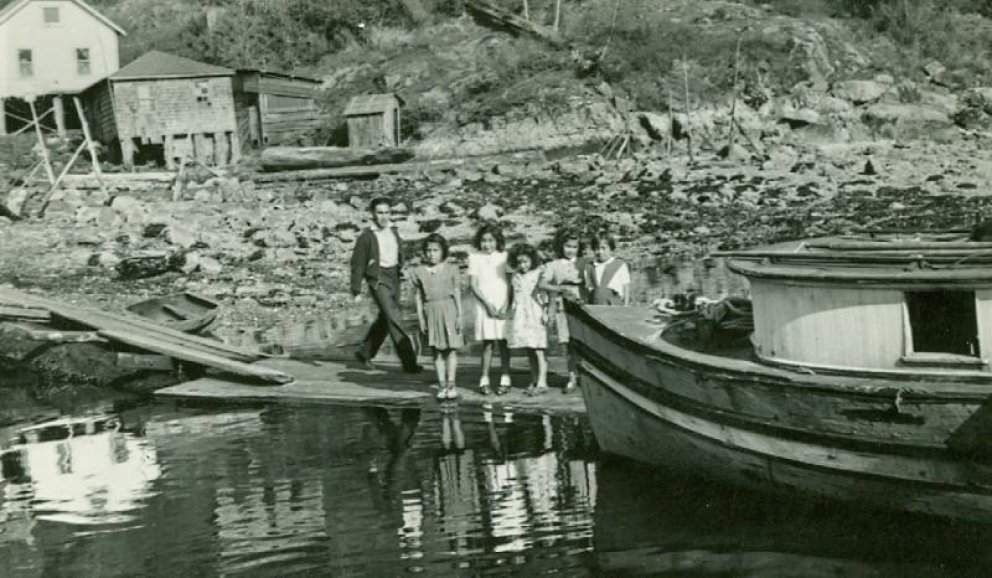

In the late 1800s, our people were moved by the Oblate priests to a site known as “Muushkin” or Old Church House on Sonora Island. Unfortunately, the village was in the path of fierce outflow winter winds and most of the buildings blew down in the early 1900s.

The Homalco people were then moved to the mouth of Bute Inlet within Calm Passage to “Aupe” or New Church House. Here there was shelter from strong winds with bountiful fishing and clam beds. These village sites are no longer inhabited, with the last people leaving Aupe in the early 1980s, but the Homalco peoples still stop at Old and New Church House occasionally. If you visit Bute Inlet with us, we’ll tell a story and perhaps share a song here.

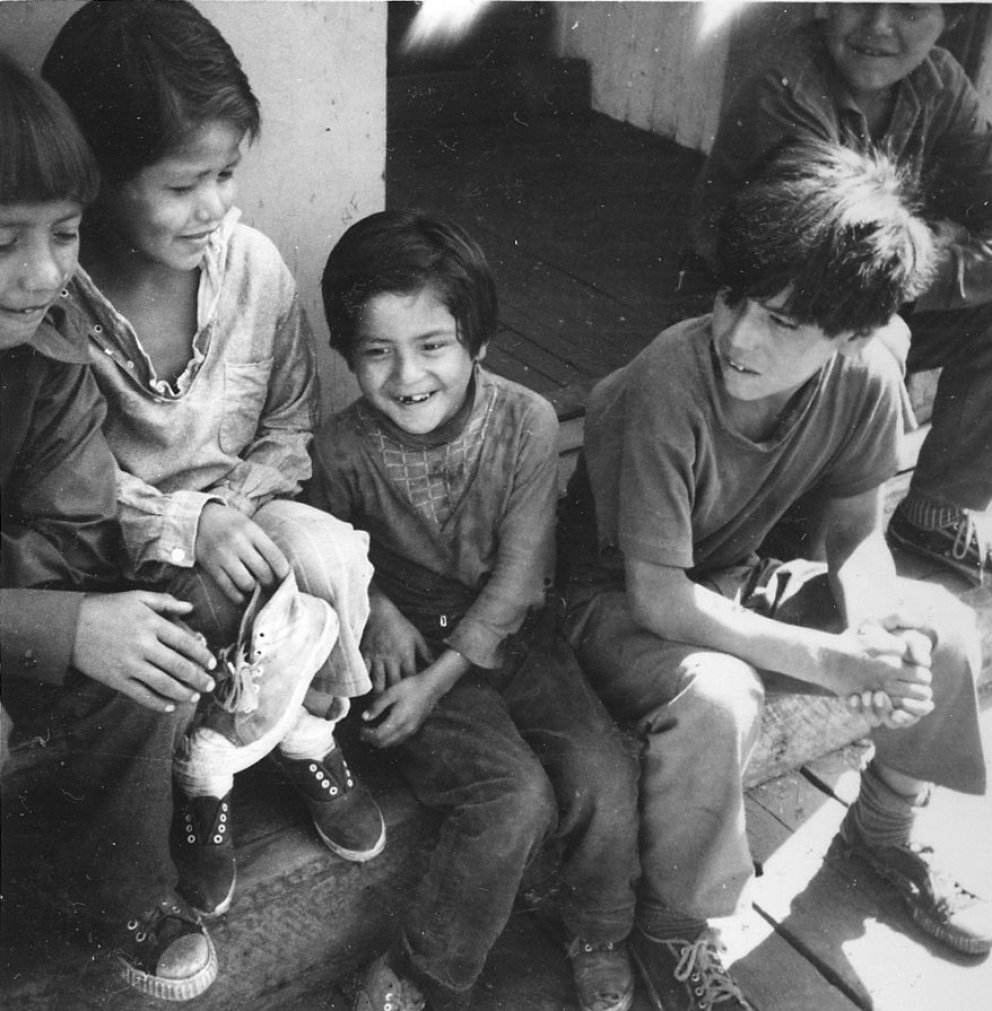

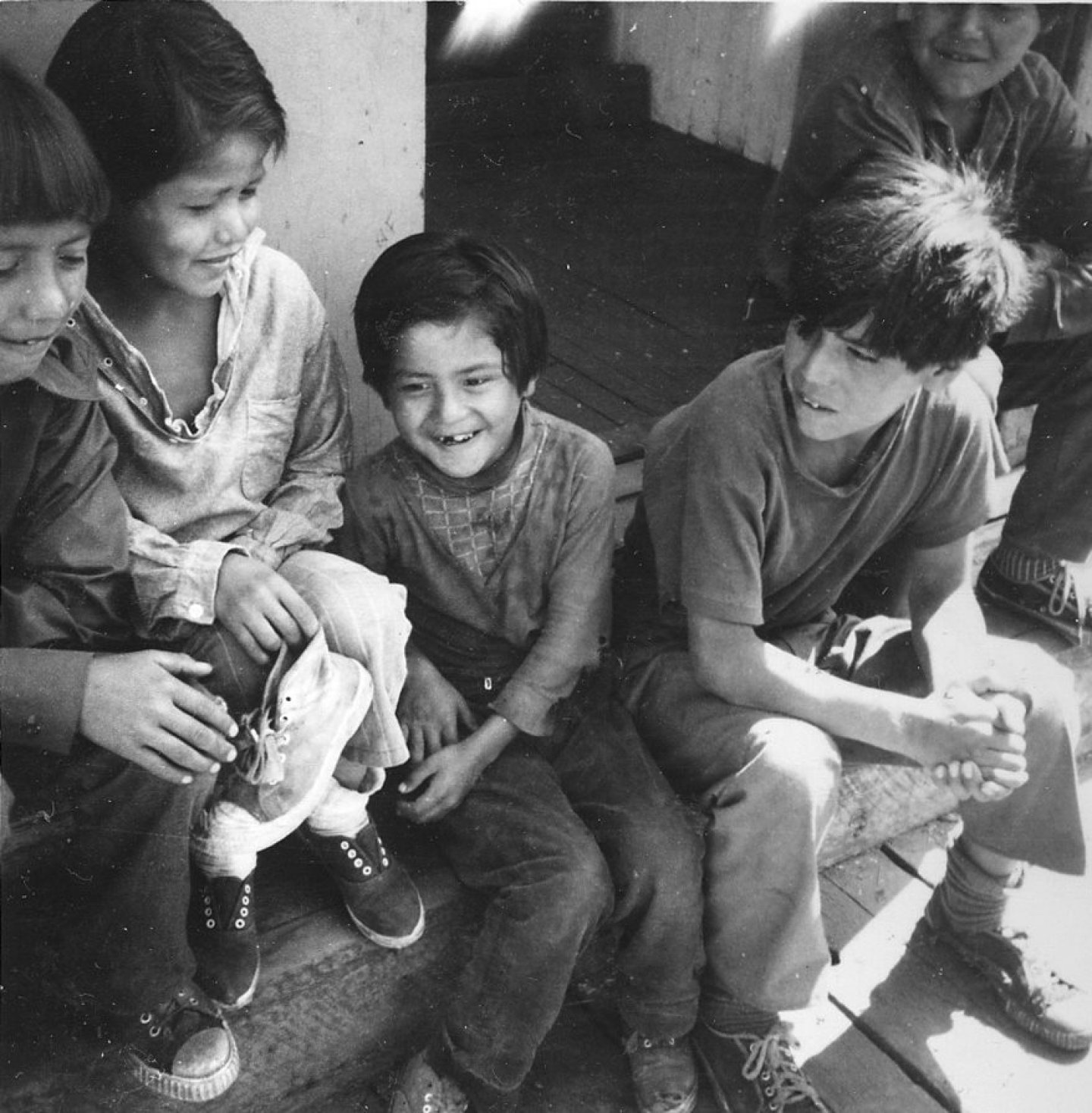

By the early 1900s residential schools were formed and implemented by the Federal Government. For generations, our children were taken from their families and forced to attend residential schools. At these schools, Xwémalhkwu people were often physically, mentally and sexually abused. The loss of these family units, culture and language and the traumas of abuse are issues that our communities still struggle with today.

Today’s Homalco

Today the Homalco people continue to be stewards of the land and rely on the resources throughout the territory. We take great measures to ensure these resources are there for future generations to come and hope to welcome guests into our traditional territories with the goal of creating advocates for our land, our culture and our language.

We work diligently to revive and rekindle parts of our culture, namely through language, gatherings and teachings that were almost lost to us. By opening the doors to Homalco, we hope to spark interest in our culture and carry forward our traditional ways of life for years to come.